The R/V WT Hogarth docked at USF CMS before we left on November 10, 2021.

If you’ve ever wondered what living at sea feels like, asking a marine scientist is good start. As a marine science graduate student at USF College of Marine Science (USF CMS), I can tell you that each cruise experience is as unique and exciting as the last. This particular cruise is my third overnight trip on a hydrographic survey – which is just a fancy way of saying we’re measuring and describing features on the seafloor. My very first cruise at USF CMS was on the same boat we’re on now, the R/V WT Hogarth, as an eager undergraduate more than two years ago, so being back onboard for this expedition carries a special weight. This is also my first official cruise as a graduate student!

As you can imagine, the embarkment is the most exciting part. Research boats usually leave early in the morning, and I typically spend the majority of the night before too excited to fall asleep. At the dock, the smells and sounds of the boat start to feel familiar as the crew gets ready for departure. Ships have small living spaces with multiple bunks in each room—so naturally, these cruises can feel like fun fieldtrips with fellow researchers who are just as excited as you are to be heading to sea. Our cruise departed in the early morning and once we passed under the Sunshine Skyway Bridge, everyone waved goodbye to land for the next six days. Off-shore, the ocean turned a deep blue as the coast faded away and the wind carried a distinct salty-freshness that instantly relaxed any anxiousness I was experiencing.

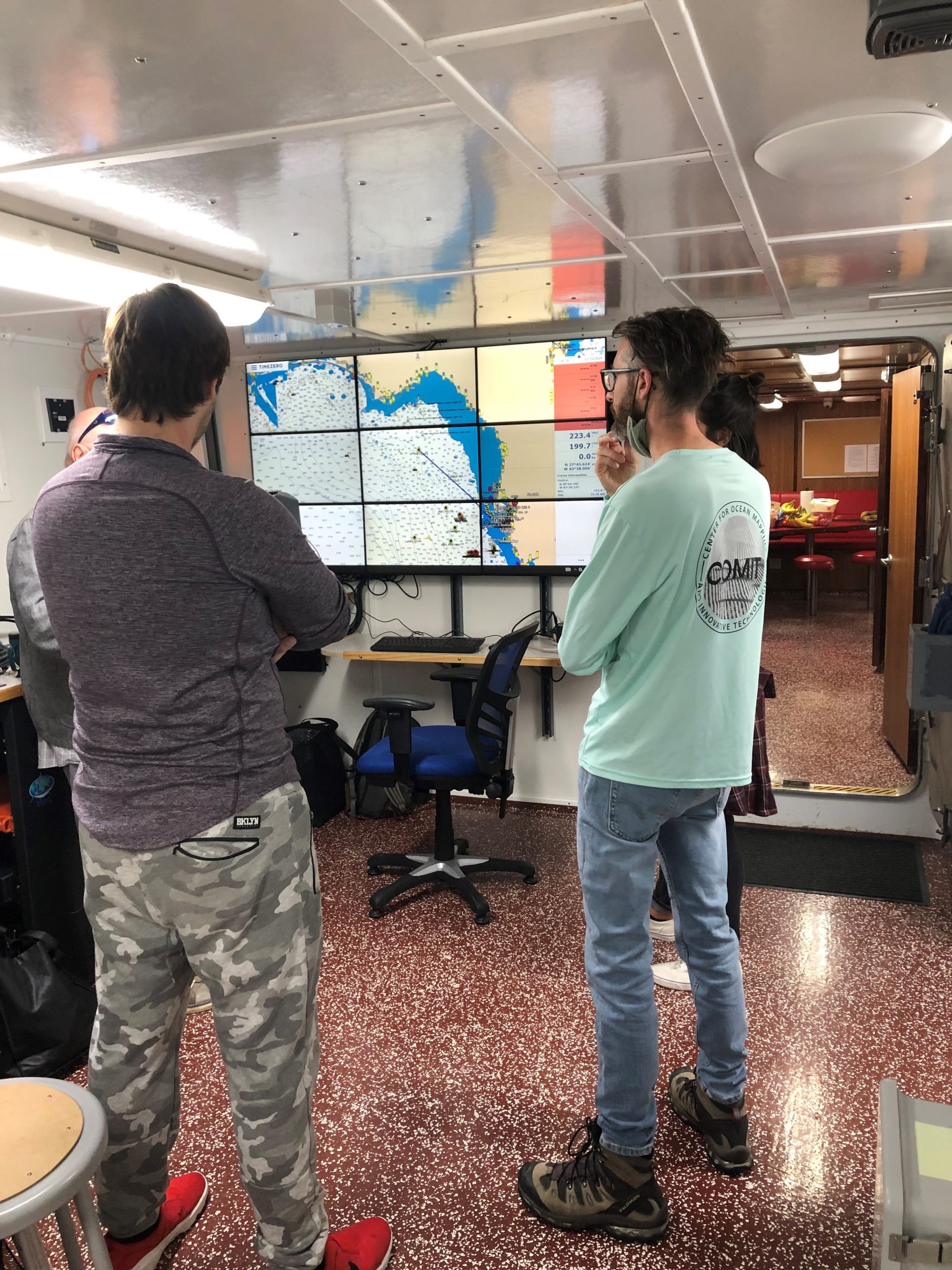

The Science Party discusses some last minute logistics before leaving port.

For this cruise, the travel time to our mapping area was close to 12 hours. During those initial hours, the crew reviewed safety procedures and got the boat settled while the science party finished setting up the mapping equipment. Hydrographic vessels use sonar, or sound waves, that work much like a bat or dolphin’s echolocation. These sound waves are emitted by a transducer mounted underneath the ship that then bounce off the bottom of the ocean and back to the ship. Using measurements for sound speed, our computers can calculate how deep the seafloor is below the boat and create a 3D map of what it looks like. For measuring sound speed, we use a device called an underway sound velocity profiler (SVP) which is towed on the back of the boat. It can be a bit tricky to deploy and retrieve while the boat is moving but it makes getting sound velocity data much easier. More traditional methods involve stopping the ship during the survey and taking time to lower a sound velocity probe all the way to the seafloor and back.

Most people might consider the ocean floor to be boring and lifeless, but any marine scientist will tell you it is so much more. Once we got to our survey site, we hit the ground running and started mapping right away and as we move along, we uncover a part of the seafloor no one has ever seen before! And that’s what makes being a hydrographer so exciting. The bottom of the ocean off the west coast of Florida is called the continental shelf. Here, we can see the remnants of prehistoric shorelines, mangrove stands, and oyster reefs among other features. Knowing this is where a giant sloth or a woolly mammoth once walked is exciting and we’re uncovering it all through the ship’s sonar! The cruise has gotten off on a good foot and we’ve already settled into a routine watching more and more data roll in, continuously building a new map. Our crew is in great spirits and I’m excited to see what the rest of the cruise has in store for our team.

Check back for another update tomorrow!

Recent Comments