Written by: Mark Mussett (MS Student)

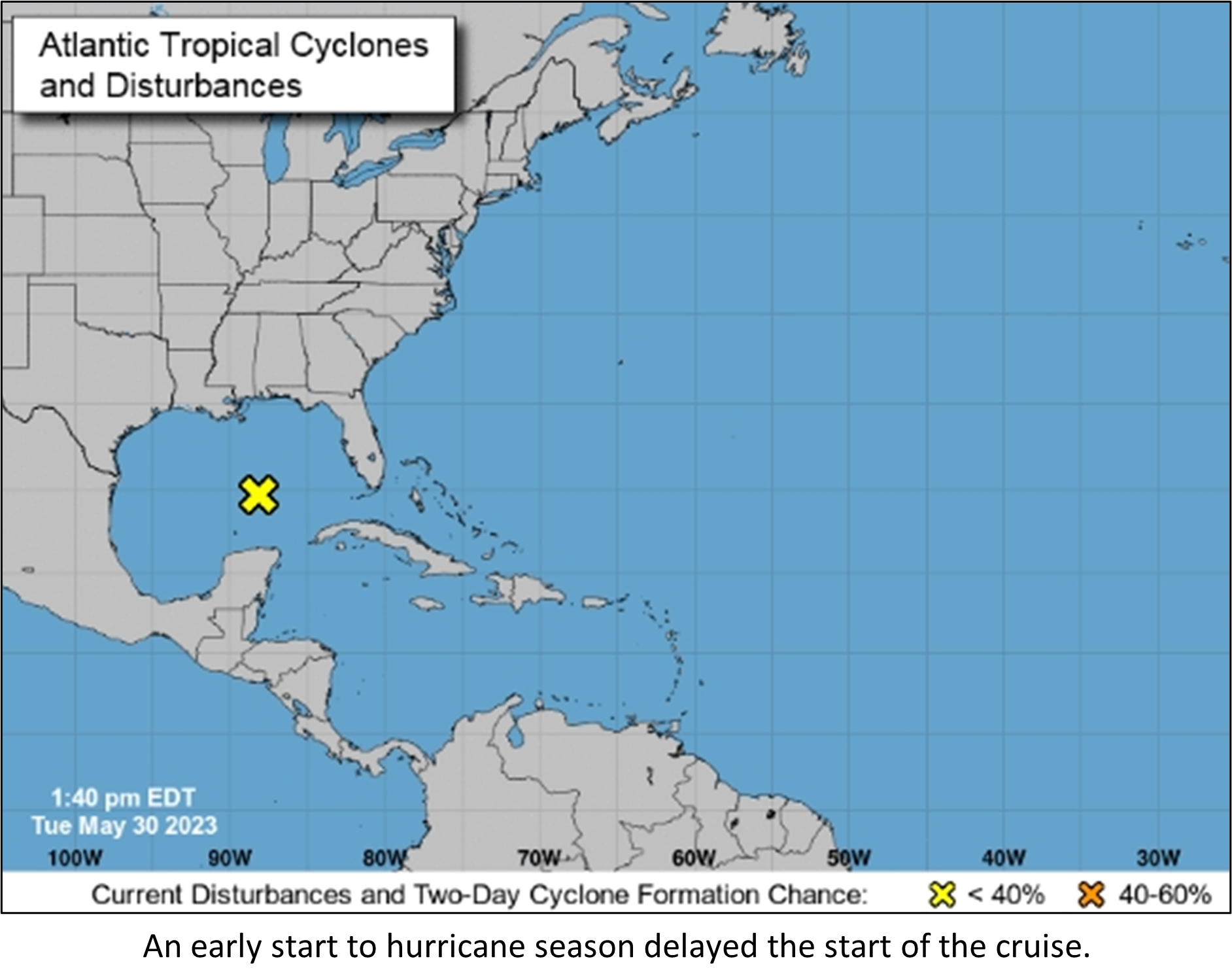

Despite a delay in the cruise schedule owing to an active start to the 2023 Atlantic hurricane season, I joined a troupe of fellow scientists and students from the CMS community to make the journey from St. Petersburg to Charleston to sail aboard the Nancy Foster in early June. We were joining the ship for the second of 4 planned cruises. The drive was a great opportunity to both become acquainted with some of the team I had not met before and catch up with those I’ve worked or sailed with in the past. I had not been to Charleston in some 10 years and was struck by the street flooding caused by a mere high tide from a near-full moon the night of our arrival. Though we would be mapping offshore, seeing this underpinned the importance of mapping, especially in the coastal environment which has been increasingly impacted by events such as regular flooding due to sea level rise.

After a long day of travel, settling on the ship quayside afforded a welcomed rest as I looked forward to forging new friendships over the coming week and undertaking my first sailing aboard a NOAA ship.

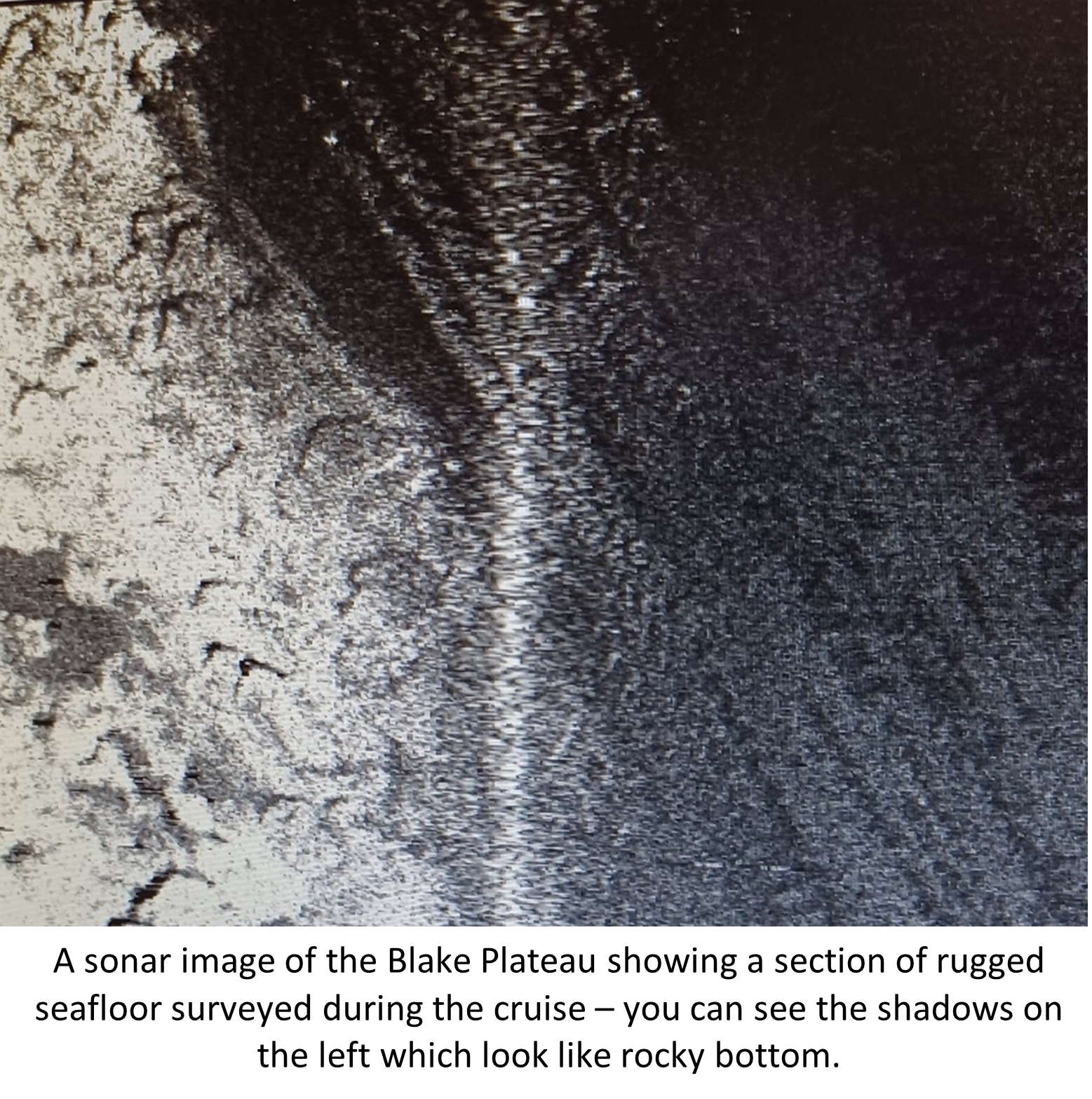

After breakfast (which was my first introduction to the amazing dining aboard Nancy Foster), I became acquainted with the ship, crew, NOAA science staff, fellow shipmates representing the College of Charleston and the University of New Hampshire, and the expectations of visiting students and scientists such as myself. Our operation would contribute to NOAA’s mission to maintain nautical charts for waters under U.S. jurisdiction, and compliment sonar mapping previously undertaken in adjacent areas. Our cruise focused on multibeam sonar data collection over a seafloor feature known as the Blake Plateau. It is a unique and geologically interesting area since proximity to the strong currents of the Gulf Stream create regions of the plateau swept clean of sediments. The result is a tapestry of minerals and benthic habitats not commonly seen on other areas of the continental shelf. Furthermore, the area underlies an important shipping lane, and the prospect of finding a previously undiscovered shipwreck imbued a sense of enthusiasm to the start of each shift during the cruise.

Later during the first full day aboard ship, when tide favored an outbound voyage, we cast off towards the Atlantic under sunny skies and a cool breeze (with a quick onboard for our last scientist via small boat). Spirits were high as we passed Charleston light and the historic Fort Sumter. The visiting scientists spent the remainder of the day settling into the rhythm of the ship, networking, and prepping for the mapping activities as the ship transited offshore to the work area, no quicker than 10 knots. Though the boat is capable of higher speed, a 10 knot top speed has been implemented in this area by NOAA to avoid collisions with migrating North Atlantic right whales.

Though there were clear scientific goals for the cruise, NOAA personnel budgeted plenty of time to accommodate training and teaching visiting science crew. They happily described the equipment, software, and methods used aboard the ship. A research ship is often where traditional and cutting-edge technologies meet, and it

was interesting to see how a simple stopwatch and level wind winch were used to keep a Bluetooth enabled CTD sensor suite (or sound velocity profiler (SVP)) from crashing into the seafloor. Without data from this equipment, it would be nearly impossible to accurately map the seafloor, even with the best of weather, since the velocity sound travels through water changes over time and an accurate calculation of this velocity is required to determine the travel time between the ship and the seafloor. As it turns out, the offshore environment is also where the best methods and equipment are still at the mercy of the elements.

Following a successful first day of sonar survey and emergency drills, the second full day in the work area saw unseasonably strong north wind which, near the Gulf Stream, is a recipe for choppy conditions and big waves – neither of which help the sonar system maintain steady orientation towards the seafloor. The ship’s crew expertly navigated the ship through rough water and stormy weather so the cruise could continue once conditions allowed.

In the interim, our work shift was spent reviewing data collected the prior day and producing digital images showing the depth, relief, and (to some extent) composition of the ocean floor. The sea state settled in the evening a bit, and a pod of dolphins played alongside the ship for a time.

As conditions improved into the third day, our survey operations resumed. The visiting crew were now familiar with the process and the workflow aboard ship, and were able to actively participate in sonar data acquisition by this point.

While we were out, the crew also sent a children’s project boat adrift in the Atlantic so its travels could be tracked, a Mola mola was spotted just off the starboard rail, and that night we were able to take in the sights and sounds of a vibrant lightning storm from the darkened bridge of the ship.

The following day during the transit back to port gear was stowed, staterooms were tidied, and contact information was exchanged between new friends ahead of an afternoon disembarkation. A long drive home, with talk of impressions and lessons from the cruise, capped the experience. I look forward to tracking the progress of the last 2 cruises, and combing through the resulting sonar data to see what new discoveries might come from our time offshore.

Recent Comments